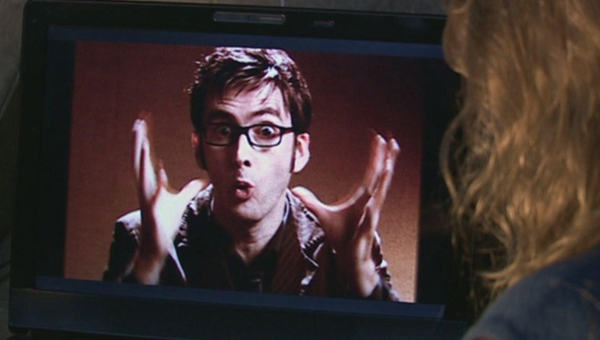

You can’t rewrite history, not one line! Or can you? Because, according to Doctor Who, time might just be a big ball of wibbly wobbly timey wimey stuff. Depending on which episode you’re watching…

In Doctor Who, the rules of time travel change almost as much as the Doctor’s face. He has been travelling through space and time for over 60 years, and in that time his take on the rules has been in flux – not unlike the space-time continuum itself.

In the early days, time wasn’t so much a big ball of wibbly wobbly timey wimey stuff as it was an immutable certainty. In the 1964 story ‘The Aztecs,’ the First Doctor famously told his companion Barbara that, “You can’t rewrite history, not one line!” He did this to dissuade her from trying to derail the Aztec tradition of human sacrifice. The Doctor insisted that it was impossible; the historical events would play out just as they did, and there was nothing anyone could do to stop them.

And he was proven right. In ‘The Aztecs,’ time was not a big ball of wibbly wobbly timey wimey stuff; it was a straight line, fixed and unchanging. Despite her best efforts, Barbara was unable to alter the path of human history.

And for many years, this stance on the rules of time travel remained unchallenged. Perhaps the first Doctor Who story to play with this idea was the 1972 adventure ‘Day of the Daleks,’ which saw a group of guerrilla time travellers travel back to the present day to try and change the dystopian future from which they’d come. They believed that if they assassinated a British diplomat called Styles they could prevent the Earth of the 22nd century from being enslaved by the Daleks.

The story became quite complicated and more than a little wibbly wobbly timey wimey, as it turned out the travellers were trying to prevent an explosion at a peace conference, but it was their travelling back to the present day that caused the explosion in the first place, creating a paradox. And so this explosion had to happen, and indeed did happen, which ties in with the First Doctor’s assertion that time cannot be changed.

At the same time, at the story’s conclusion, the Third Doctor tells Styles that the dystopian future overseen by the Daleks is not a certainty, and that it can be prevented. But it’s up to him and the rest of humanity to make it happen.

Time, therefore, can be altered in this scenario. Why? “Wibbly wobbly timey wimey,” as the Doctor might say. Certainly, this idea that time is ever-changing became the mainstay of the classic series. In ‘Pyramids of Mars,’ the Fourth Doctor shows his companion Sarah Jane a dystopian version of the year 1980 – a barren wasteland brought about by the wrath of Sutekh the Osirin. He tells her that this future is certain unless he and Sarah can defeat Sutekh, which they do.

And then of course there is perhaps one of the most wibbly wobbly timey wimey stories of the classic run. In ‘City of Death,’ Scaroth the Jagaroth is trying to travel back into prehistory to prevent the explosion of his spaceship – an explosion which gives birth to the human race. The Doctor must stop him or humanity will never have existed. Moreover, Scaroth has influenced the whole of human history, playing a part in the invention of the first wheel and the construction of the pyramids. Without him, the history of planet Earth will change forever.

It’s worth noting that this occurrence would also have erased the Aztecs, thus nullifying the First Doctor’s promise that time cannot be rewritten, if your brain isn’t hurting enough already. So what are we to make of all this wibbly wobbly timey wimey confusion?

The generally accepted rule from the new series (2005 onwards) is that, whilst time can be rewritten, there are certain events which are fixed, and cannot be changed no matter what happens. And Time Lords are sensitive to these events; they simply ‘know’ which ones are fixed, and messing with them can have dire consequences.

For instance, in the 2005 episode ‘Father’s Day,’ Rose manages to prevent the death of her dad Pete Tyler and change the course of her own personal history. This causes a serious problem – far greater than a simple wibbly wobbly timey wimey headache. It attracts the reapers, who are a bit like antibodies who tend to ‘wounds’ in time by cleaning up the damage left behind. In Rose’s case, these wounds are the human race. The only way to make them retreat is for her father to die and repair the damage to the timeline.

And whilst this occurrence does raise the question as to why the reapers don’t appear every time someone makes a radical alteration to the timeline, the explanation given in ‘Father’s Day’ is that the moment of Pete Tyler’s death was a vulnerable point in space and time, owing to the fact that there were two sets of the Doctor and Rose in attendance (it will make sense when you watch it.) So the reapers are not always guaranteed to appear.

Even then, such is the wibbly wobbly timey wimey nature of the cosmos, it’s still best not to tinker. For example, in ‘The Wedding of River Song,’ River interferes with the apparent death of the Time Lord at Lake Silencio and sends everything into disarray. There aren’t any reapers, but she causes all of human history to happen all at once, with Roman centurions queuing up at 21st century traffic lights, and Charles Dickens promoting his Christmas stories on BBC News. It’s carnage.

The general rule, therefore, in the wibbly wobbly timey wimey world of the Whoniverse, is that certain events cannot be rewritten, and some can. The First Doctor was right, in a way, although his later adventures demonstrate that some moments can indeed be altered. The key is to not mess with the important ones, otherwise you’ll ruin the entire world as River did, or bring forth an army of ravenous reapers.

What do you think about the wibbly wobbly timey wimey nature of the Whoniverse? Does it contradict itself, or does it all make sense? Let us know in the comments below.

Leave a Reply